Following its move to Westchester over the 1996-1997 winter break, Otis College took on a new identity—more students, evolved pedagogy, a stronger sense of community—but the heart it brought from MacArthur Park lives on.

By Lisa Butterworth

Aerial view of Otis College's Goldsmith campus in Westchester.

When people think of Otis College of Art and Design’s campus, the impressive Kathleen Holser Ahmanson Hall often comes to mind. The seven-story building, with its grid of small windows and boldly angled concrete piers, is one of the architectural hallmarks of Otis’s Westchester location, and with good reason, considering its pedigreed past. The structure was designed as IBM’s aerospace headquarters by renowned industrial architect Eliot Noyes, with the help of famed mid-century modern Los Angeles architects A. Quincy Jones and Frederick Emmons, who were inspired by the company’s punched cards, pieces of paper that held digital data in the early days of data processing.

But these details, which make Ahmanson an iconic local landmark, aren’t what immediately come to mind when Joan Takayama-Ogawa recalls her first impression of the 1964 building. Takayama-Ogawa, a celebrated ceramicist and Otis faculty member, was a part-time staffer in 1997 when it was announced the campus would move across town from its original MacArthur Park location, where she had begun taking Extension classes 1986. She distinctly remembers the day when then-President Neil Hoffman took staff members on a tour of the new facility. “The building had been vacant for years, and pigeons were flying inside! I just said, ‘Oh my God, you’re kidding,’” Takayama-Ogawa says with a laugh. Much has changed since then.

This year marks the 25th anniversary of that momentous move, which allowed Otis College to grow and evolve in ways only this new location could make possible. Here we take a look back at where Otis College was, how it has evolved, and perhaps most importantly, what has remained the same.

Despite the former IBM building’s exposure to the elements, Takayama-Ogawa could see its potential, which is exactly what the move afforded Otis College and why it was championed by Elaine Goldsmith, who chaired the Board of Trustees from 1983 to 1998. The school was able to expand academic offerings, and has since nearly doubled its student population. With the opening of the Westchester campus, aptly named the Elaine and Bram Goldsmith Campus, two new vital majors were also launched: Toy Design and Digital Media.

Ahmanson Hall was just the beginning. The Bronya and Andy Galef Center for Fine Arts, designed by Los Angeles architectural firm Frederick Fisher and Partners (Fisher is a member of Otis’s Board of Trustees), opened in 2001. In 2010, Otis acquired the North Building for its Product Design program, expanding the Goldsmith campus to an entire city block. In 2021, the building was renamed the Mei-Lee Ney Design Studio, in recognition of current Board of Trustees chair Mei-Lee Ney and her $10 million gift to the College. And in 2016, the Academic Building opened, now renamed the Anne Cole Building, which houses the Fashion Design program, the Millard Sheets Library, and the campus’s first residence hall, offering housing to 200 students while fostering the school’s thriving sense of community.

“Everywhere you went, somebody was making something right in front of you. There was paint everywhere. You could see somebody outside using the foundry, or you were walking past somebody doing ceramics, or talking to you about fashion. It felt like a very creative place, 100 percent, all the time.” —Dawn Bailli

That feeling of community is inherent to Otis College and began with its original campus, near MacArthur Park. If Ahmanson Hall is the calling card of the Westchester campus, it was the massive mural by famed artist and Otis College alumnx Kent Twitchell (’77 MFA Fine Arts) that identified the MacArthur Park campus for many, including current Board of Trustees member Dawn Baillie (’86 BFA Communication Arts, Illustration), who started taking classes there in 1982. The mural, Holy Trinity with the Virgin, which remains today, was painted by Twitchell for his master’s thesis in 1977 and overlooked the campus’s parking lot. “I lived in Hollywood and drove into school every day; that [mural] would be the first thing I saw,” Baillie says. “[I remember] just being in awe of the expertise of it, and wanting to be able to do that sort of thing.”

Otis College alumnx Kent Twitchell’s mural-in-progress, Holy Trinity with the Virgin, at Otis’s MacArthur Park campus, left, which eventually became the Charles White Elementary School, right.

The mural was one of many elements that made Otis College feel like “exactly what an art school should feel like,” says Baillie, who has since founded BLT Communications and designed some of the entertainment industry’s most memorable movie posters. “Everywhere you went, somebody was making something right in front of you. There was paint everywhere. You could see somebody outside using the foundry, or you were walking past somebody doing ceramics, or talking to you about fashion. It felt like a very creative place, 100 percent, all the time.”

Chris Warner, a Foundation program instructor, agrees. He was teaching life drawing and anatomy part-time at the MacArthur Park campus, which he calls “a very lively place,” in part because the location included the Fashion Design program, which didn’t relocate to the Goldsmith campus until 2016 after an interim location in downtown L.A.’s fashion district. “I remember the fashion students being such a vital part of the experience there, in all of their extravagant dress and style—colorful, crazy homemade stuff,” he says, recalling the punk movement that ruled the look of the era. “I really got a lot of energy and excitement out of that locale… But there was an incredible amount of crime happening there—you really had to watch your back. But at the same time it was a pretty inspiring place to work. It was so gritty, [especially] compared to the new, grand space we’re in now. It was a 180-degree shift, in terms of [the campus] now being really, really nice and organized and clean.”

“I think that’s the best way of describing Otis, at the old campus and at the new campus—there’s a lot of love in the air. A love for a subject matter, a love for what we do, and a love for one another.” —Joan Takayama-Ogawa

The move to Westchester, which happened over the holiday break of the 1996–1997 school year, was also incredibly organized, Takayama-Ogawa recalls. Walkie-talkies were a crucial component in those pre-cellphone days, and a fleet of moving vans, headed by a foreman named “Bubba,” arrived in MacArthur Park. Each van was clearly designated for a specific major and floor of the new Westchester campus, then loaded up with boxes and equipment. Takayama-Ogawa shares one particularly memorable image from the event: “The Natural History Museum used to give us animals, like stuffed antelope and a taxidermied zebra, the head of a giraffe. All these animals were on carts, and they were being rolled into the moving van, and it really looked like they were entering [Noah’s] Ark. I remember shouting, ‘Noah, you’ve got a lot of work ahead of you!’ And Bubba yelled back, ‘Nothing compares to moving an art college!’”

The metaphor proved to be more apt than expected when it began to rain during the move, and the moving crew, along with all of the faculty members who had volunteered to help, arrived at the new campus amidst a torrential downpour. “It was almost biblical,” Takayama-Ogawa jokes. But no one was deterred—the vans were unloaded and the following weeks gave way to a flurry of unpacking and organization. “It was all hands on deck. Even the Board of Trustees came and helped,” Takayama-Ogawa says. The school opened on time for the beginning of Spring semester, and Otis College’s new chapter began. “It was just euphoric,” Takayama-Ogawa recalls. “It was a time of Thanksgiving. It was quite wonderful.

“There are classes we have now that never would’ve been taught before. And I think we’re also moving to a pedagogy that will accommodate the student of today, as opposed to the student of 25 years ago.” —Marsha Hopkins

For Liberal Arts and Sciences faculty member Marsha Hopkins (’97 BFA Fine Arts, Painting; ’02 MFA Writing), the move wasn’t quite so smooth. As an undergrad, she was part of the old campus’s last graduating class, and received her MFA in creative writing as a member of the first class to graduate from the new campus. Students were expected to move their own studios, and she laughs recalling how heavy one of her steel and concrete sculptures was. “Little by little, it’s come together nicely,” she says of the Westchester campus, where she’s been teaching since 2002. “There are classes we have now that never would’ve been taught before. And I think we’re also moving to a pedagogy that will accommodate the student of today, as opposed to the student of 25 years ago.” She cites Elaine’s, the large dining common, as another upgrade current students get to enjoy, though she has fond memories of the tiny kitchen cafe that served hard-boiled eggs and peanut butter and jelly sandwiches on the MacArthur Park campus, and the cookies that were baked every day. “About two o’clock in the afternoon, we could smell the cookies as they were baking,” she says. “Needless to say, as soon as you could, you went and bought cookies.”

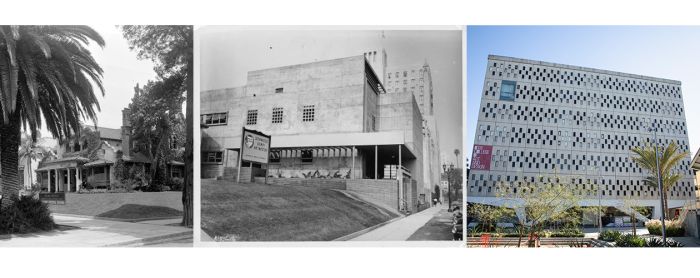

Three iterations of Otis College’s main campus buildings, from left: the home of Harrison Gray Otis near MacArthur Park, dubbed the Bivouac, which he donated for the founding of what originally was called the Otis Art Institute of the Los Angeles Museum of History, Science, and Art; the Bivouac was replaced by a modern building in the 1950s (middle); the Kathleen Holser Ahmanson Hall in the former site of IBM’s aerospace headquarters, which was designed by architect Eliot Noyes in 1964.

Despite Otis College’s move, growth, and evolution, some things remain unchanged, and according to Hopkins, that’s for the best. “For me, Otis is the idea that as a student, I can talk to anyone on campus and be comfortable. The fact that the president comes in casually and starts a conversation with you,” she says. “There has always been that personal connection to your faculty, to your instructor. That’s pretty much the same.”

Takayama-Ogawa relays a similar sentiment. “Someone was watching my class on Wednesday night, she was an Extension student, so she had never been on campus much. And she said, ‘There’s a lot of love in the air here.’ And I think that's the best way of describing Otis, at the old campus and at the new campus—there’s a lot of love in the air. A love for subject matter, a love for what we do, and a love for one another.”

Although the original MacArthur Park campus could not have supported the Otis College of today, it provided an incredible foundation from which the school could grow, starting with the faculty and extending to the students, some of whom, like Hopkins and Takayama-Ogawa, are instructors today. “I think the old campus represents a tremendous legacy,” Warner says. “You think about Charles White, Betye Saar, all of the people who taught there, or went to school back in that location. Hopefully that is inspiring and fueling our current generation of artists and designers here in this brand new, very upgraded physical plant. But a building’s a building. It’s a nice clean building or it’s an old decrepit building. It’s the quality of the people and the students who are operating within it that counts, and that, thankfully, is something still intact.”

Are you an alumni and/or faculty member who remembers when Otis College moved from MacArthur Park to Westchester and have stories to share about that time in the College’s history? If so, drop us a line at communications@otis.edu and tell us your stories!

A statue of Harrison Gray Otis in MacArthur Park that points to the site of his former home and Otis College’s first campus.