Lynell George Reflects on White’s imprimatur on his former students at Otis—now artists in their own right—and the lessons that still can be learned from his life and work.

By Lynell George

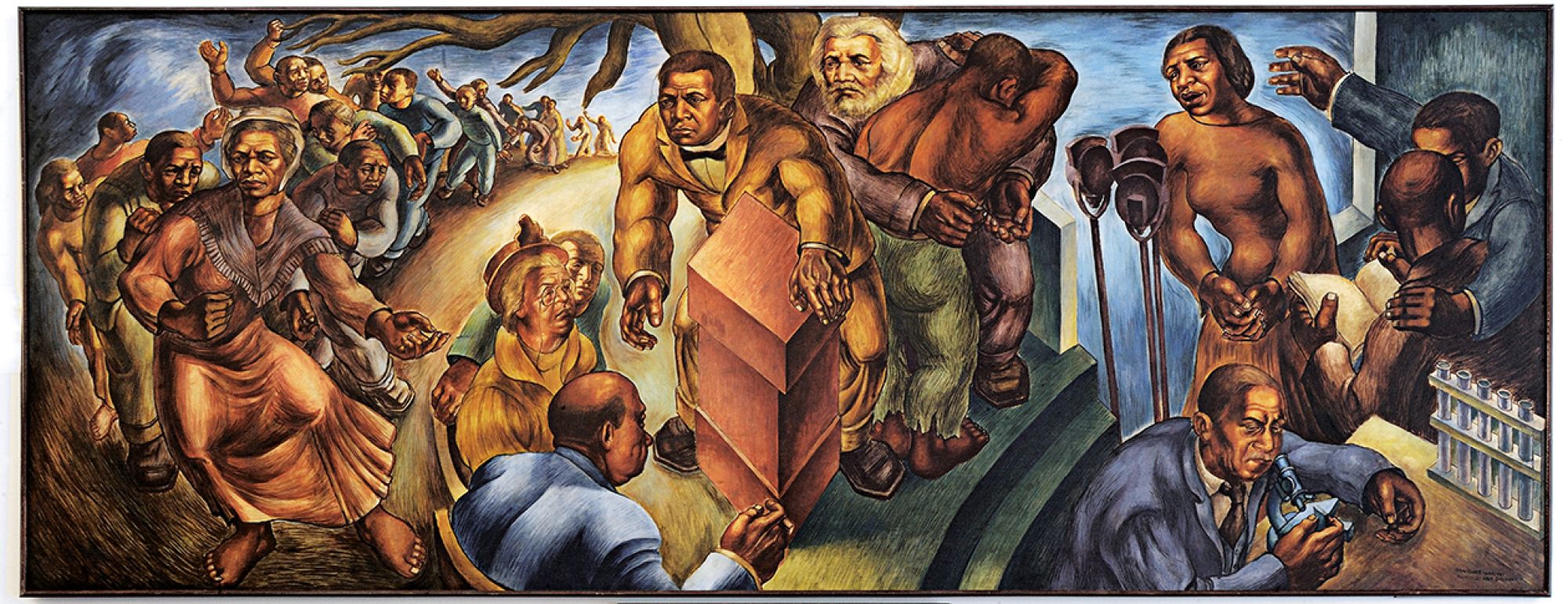

Charles White’sFive Great American Negroes (1939), his first public mural,includes Black heroes Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington, Fredrick Douglass, George Washington Carver, and Marian Anderson.

What is legacy and how does it echo? Through time? Through us? A culture?

Over the course of this past year, against the dire backdrop of a pandemic, many of us have been compelled to think more about evanescence and what the notion of legacy might mean. Complicating the landscape, last summer, a protracted season of racially motivated violence launched a succession of impassioned protests across the country: On screens large and small, we watched, spellbound, as a nation’s frayed social fabric continued to unravel.

There was a deeply poignant familiarity to the tableau: fists thrust upward, voices raised, an ache was reawakened. As urgent and of-the-moment it all seemed, there was indeed something all too familiar in the display. In the wake of the brutal police killing of George Floyd—a Black Minnesota man—these around-the-country marches, vigils, and candlelit gatherings served to frame inchoate emotion, to push back against a form of police brutality that, agonizingly, recurs time and time again.

On a sticky June afternoon, tucked away here in Southern California in my quarter of Northwest Pasadena, I could hear the rhythmic chants of Floyd’s name through the gaps in my own windows, as residents took to the streets. Curious, I went scrolling, searching local news feeds to see where the procession had chosen as its end-point. I landed on the location, Charles White Park, mere minutes away in Altadena.

That this park was a key gathering place, a safe collective space to convene, to voice fury, express grief, or float wishes, was beyond symbolic—it was the continuation of a sentence, of a wish. It would have most keenly meant something to the artist himself, for whom the grounds are named, in a city in which he had made his home. Throughout his long career, White’s guiding principle was to “reflect deep and abiding concern for humanity.”

“Paint,” White declared, “is the only weapon I have with which to fight what I resent. If I could write, I would write about it. If I could talk, I would talk about it. Since I paint, I must paint about it.”

He was shaped by his own struggles: growing up in severe poverty, navigating a country’s repudiation of equity and freedom “for all.” His ambition enabled him to push beyond any limits the outside world had arbitrarily set for him. And, in turn, he would educate others, passing on tools to face the moment, tools of creative survival as a committed educator.

It is possible to make a portrait with the gifts of legacy. Those deeds and words become textures, hues, strokes, and shadings. Memory assembles itself into an afterimage that reflects that richness, and the depth and breadth of the impact a single figure may have on people, place, and practice.

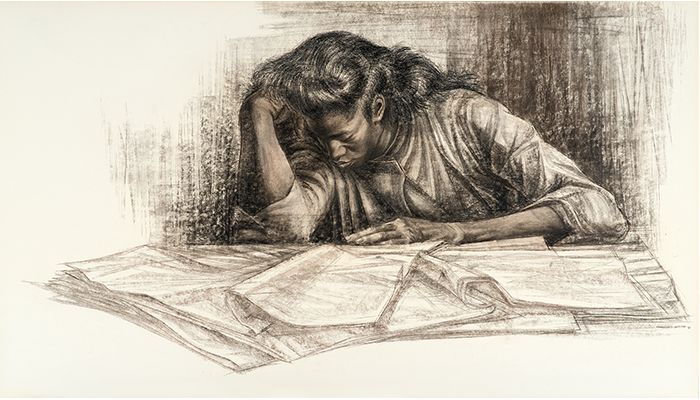

Prophet I (1975) by Charles White

White as Teacher

Charles Wilbert White (1918-1979)—drawer, painter, and printmaker—cut an impressive, boundary-shattering figure in the art world, and proved a real-world example for his students. Many of them—David Hammons, Kent Twitchell, Judithé Hernandez, Kerry James Marshall, Suzanne Jackson, and Richard Wyatt, among them—have gone on to attain their own acclaim and, with it, a particular cache. But perhaps, most importantly, they acquired a way of looking at the world and helping us to see it in all of its revelatory contours and uncomfortable contractions. Back then, when they crossed into White’s sphere, they were looking for instruction in their field of study, but also for a way to be the world.

In his 15-year tenure at what was then called the Otis Art Institute, White’s classes were wildly popular, and often over-subscribed. Hammons, for one, remembers making a bee-line, seeking him out on the MacArthur Park-adjacent campus in 1968: “He’s the only black artist I really relate to... because he is black and I am black,” Hammons recalled in an artist statement. But that recognition went beyond skin-deep. Hammons had surmised another layer of kinship: “In most of Charles White’s art there aren’t too many people smiling…. There’s also a kind of agonized look... I think because there aren’t many pleasant things in his past. He’s gone through a lot of Hell. I know he has.”

This is recognition beyond a flicker of the familiar. White’s presence was permission. For his students, it presented a potential path and a way of envisioning a self that was beyond even their own expectations. There was nothing more powerful than seeing a possibility take real form.

Awaken from the Unknowing (1961) by Charles White

White, widely known for his epic Works Progress Administration-era murals, paintings, and his distinctive and signature oil-wash technique drawings depicting a wide spectrum of Black life, was a deeply committed activist across the great sweep of his varied career. While his subject matter was often considered insurgent if not radical, his style, steeped in social realism, was considered “retrograde” or anachronistic for the moment he occupied. When abstract expressionism was the mode of the moment, White cleaved to realism’s accessibility. “[His] commitment to realism is unwavering,” writes art historian Kellie Jones in South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s “To him it represented an art language.”

At its core, the work conveys, and frequently returns to, notions of self-determination and resilience, freedom and humanity, courage and affirmation of life—Black life. Dignity is another key characteristic associated with White’s work, and was the centerpiece of the title of his first monograph, Images of Dignity: The Drawings of Charles White, in 1967. But to suggest that White’s work was simply about uplift obfuscates the deeper complexity of his efforts to convey the struggle of simply being seen as human—whole and complete.

White used his practice to raise not just awareness and concern, but his own eloquent voice: “Art must be an integral part of the struggle. It can’t simply mirror what’s taking place. It must adapt itself to human needs. It must ally itself with the forces of liberation. The fact is, artists have always been propagandists. I have no use for artists who try to divorce themselves from the struggle.”

“The fact is, artists have always been propagandists. I have no use for artists who try to divorce themselves from the struggle.”

In 2018, the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art in New York organized Charles White: A Retrospective, the first major exhibition of White’s work in more than 30 years that also traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art the following year. It offered room upon room of drawings, paintings, personal photographs, busy sketchbooks, and heroic and elegiac mural studies that expressed a wide-ranging, curious mind. In a review of that show in Alta: A Journal of California, critic and art historian Carol Strickland reflected: “What remains the same throughout his transit from stylized realism, to naturalistic realism, to what might be called mysterious realism is White’s commitment to social justice.”

From the outset, White’s mission was clear: a commitment to reframe a narrative, supplanting degradation with racial pride and inspiration. He found a declarative voice in his art to counter racism and tip perceptions. One of his most famous pieces, Five Great American Negroes (1939), his first public mural—for which he sought input on “who contributed most to the race”—includes Black heroes Sojourner Truth, Booker T. Washington,Fredrick Douglass, George Washington Carver, and Marian Anderson and was an attempt to bring visibility to the achievements and resilience of African-Americans during a climate of dismissal and abasement.

The Artist’s Beginnings

Born in Chicago in 1918, White was transfixed by the arts from an early age. His mother, who worked as a domestic, would set him up with librarians she had befriended at the public library before she sped off to work. It was his safe space. Young Charles, who would become a voracious reader, plunged deep into his imagination. Before long he found himself on a side path. He sat at the tables sketching shapes and textures, shadows of figures. His mother eventually bought him his own set of oil paints, but, without instruction, he didn’t know how to use or care for them. By chance, he encountered a group of artists from the Art Institute of Chicago in a nearby park and studied them and their technique from afar.

While the paint set both distracted him and diverted him from trouble in his South Side neighborhood, his mother worried about the focus. Her son showed immense talent, but a career in art, for a Black boy, seemed a fixation to be shelved in the library’s fantasy section. She took away the paints for a time and tried to re-track his interests with other extra-curriculars like violin classes, hoping he might find a more suitable trade that would put him on a path for work. But art won and by his final year in high school he was awarded a scholarship to attend the Art Institute of Chicago, which placed him squarely on his own road.

While his frustration with racism might have been a motivating force in his work, it was in his art and in his practice that White found relief, centering it around the celebration and documentation of the contributions of Black people and culture—women, men, and children. His art was a shelter and a balm. It was a way to make a place for his disparate emotions and his own impatience about how slowly the world tipped toward change for good.

By the time White arrived in Los Angeles from New York in 1956 with his social worker wife Frances Barrett, he was an artist of great acclaim. He’d shown work around the world and cultivated relationships with artists, musicians, and actors in the respective cities he had called home. He’d lived in Mexico with his first wife, artist Elizabeth Catlett; had painted murals; and been the recipient of various fellowships and honors. Los Angeles brought him a set of new lines on his resume: a Hollywood connection (his work was featured in films);a gallery to represent him and his work after leaving ACA Gallery in New York;and the longest affiliation with an institution in his lifetime, at Otis (the Charles White Elementary School in MacArthur Park sits in Otis College’s original campus).

But moving West didn’t eliminate the ravages of racism. When the Whites moved into their new home in the San Gabriel Valley, neighbors, “furious” that an interracial couple now occupied a house on their street, almost immediately put up For Sale signs on their lawns. It would be fodder.

While the cross-country relocation distanced him from the heart of the civil rights struggle and the core group of friends, artists, and activists with whom he’d aligned himself in Chicago and New York, White kept close watch on the marches throughout the South and the violence erupting in cities. That urgency found expression in his work.

One of the few Black artists to acquire formal representation, with Benjamin Horowitz of Heritage Gallery in Los Angeles, White’s coup positioned him in a rarefied circuit. “This professional success made him a beacon,” writes Jones. “Charles White had commanding East Coast credentials, he was a singular figure who coalesced a community as the 1950s became the 1960s.”

White carried this charisma and energy into the classroom and into building sturdy alliances and connections across Southern California. He gave his students tools—those to approach their work mechanically, and a way to approach the world mindfully, much of it rooted in a way to travel a landscape that was not often easily navigable or kind. In the late 1970s he opened his home to serious students on weekends and evenings to further their discussions. And when he became chair of Otis’s drawing department in 1978, the position made him responsible for both teaching and administration, shaping and shading the present into the future.

“No one has inspired my own devotion to a career in image making more than he did. I saw in his example a way to greatness.” —Kerry James Marshall

“Nobody has drawn the black body with more elegance and authority, “Kerry James Marshall reflected in an essay commemorating White’s 2018-2019 retrospective. “No one has inspired my own devotion to a career in image making more than he did. I saw in his example a way to greatness. Yes. And because he looked like my uncles and my neighbors, his achievements seemed within my reach.”

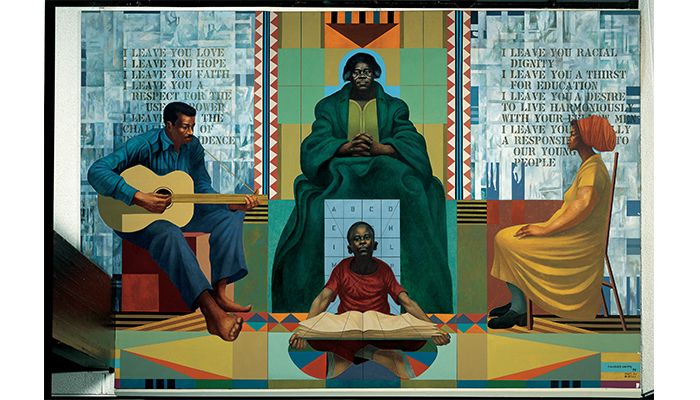

The echo of White’s legacy reverberates still here in Southern California. In his final years, he was appointed by then-Governor Jerry Brown to be the founding commissioner of the advisory board for the newly funded California Afro-American Museum of History and Culture (now known as the California African American Museum, or CAAM). As well, his stirring mural dedicated to educator Mary McLeod Bethune now graces the entryway of a Los Angeles public library branch in Exposition Park not far from the CAAM campus.

Mary McLeod Bethune Mural (1977-1978) by Charles White

But it wasn’t just the formal and/or high-profile installations and appointments that mattered to White. An equally if not more essential thread of his legacy was his commitment to accessibility and ubiquity. His work could be found on album covers and was included in motion pictures. Growing up, my household held a special place for the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance calendars he illustrated, pressed onto cork boards that were placed over the phone nook. Some of my mother’s friends would carefully detach the pages and frame the images of stoic Black faces to be hung formally in the home. These ways of spreading his vision far and wide allowed him to move beyond the elite borders of galleries and museum spaces. Rather than taking something away (as did much mainstream pop culture imagery of the time), his work gave something back to Black people—their spirit and soul: “The recognition which I seek,” he reflected, “is getting my work before more and more masses of people.”

White in This Moment

As I watched the winding masses making their long Black Lives Matter trek to Charles White Park last summer, a question circled: How would this moment—this emphatic call for racial reckoning—have been envisioned by White in his work? Now, I realize the better question would be: What were the many ways that he’s already shown us that Black lives matter?

White’s visual legacy makes clear that he never gave up on the power of people—regular “anonymous” folk—working together. And while he might have, like the generations following him, become infuriated by the pace of change, he knew that the only way forward was to keep moving—tending to the tribe, fueling the spirit of a community’s well-being.

His commitment lives most vividly in the expressions of those he mentored, those who have echoed and embroidered upon his themes and, in so doing, carried him forward. For many of them, as Kerry James Marshall reflected, the journey began with demystifying the idea—and role—of an artist, which could only begin by seeing and inhabiting one’s full self: “Under Charles White’s influence, I always knew I wanted to make work about something: history, culture, politics, social issues. It was just a matter of mastering the skills to actually do it.”

Artwork courtesy of the Charles White Archives Inc.

Lynell George is an L.A.-based journalist and essayist. Her most recent book, A Handful of Earth, A Handful of Sky: The World of Octavia Butler, was published by Angel City Press in October 2020. She also recently contributed to the anthology, Speculative Los Angeles, which was published by Akashic Books in February.